Dr. Zickgraf’s primary focus is on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, (ARFID), an eating disorder characterized by restrictive eating that isn’t related to weight and shape concerns. She has been instrumental in creating a variety of screening tools for use in the research setting as well as guiding clinical assessment of disordered eating/eating disorders in GI conditions.

Here is my informative interview on Dr. Zickgraf’s work.

Kate: Dr. Zickgraf can you tell us a bit about the work you do and the research you are most interested in?

Dr. Zickgraf: I’m broadly interested in eating behavior, and how people choose what and when to eat. As a clinical psychologist, my focus is on eating behavior, food choice, and food preference that becomes problematic and leads to weight, nutritional, or psychosocial impairment. Although I’m interested in all eating disorders and all ends of the weight spectrum, I’m most curious about eating disorders that don’t involve eating restrictions motivated by concerns about body weight and shape.

This has led to research on disordered eating that develops in the context of food insecurity (do people who restrict their food intake to conserve food rather than to lose weight develop loss of control eating behaviors similar to those that develop as a consequence of weight-related restrictions?) orthorexia nervosa (a proposed, and controversial, new eating disorder diagnosis characterized by obsessive preoccupation with “healthy” eating–but “healthy” turns out to be very hard to separate from “promoting weight loss,” particularly for people whose BMI is in a range that others label as “unhealthy”), vegetarianism (my collaborators and I wrote a paper intended to show that vegetarianism isn’t a risk factor for disordered eating, a myth that has been floating around in the eating disorder literature since the 80s. We found that motives for vegetarianism matter–not surprisingly, it’s only associated with disordered eating in people who became vegetarians to lose weight), and to my main area of focus, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).

ARFID is a diagnosis that was added to the DSM-5 (the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, where all currently recognized psychological disorders are listed and described) in 2013 based on a clinical need — up to 70% of patients in treatment for disordered eating didn’t meet the diagnostic criteria for anorexia or bulimia nervosa, the only eating disorders recognized by the previous version of the DSM. Some of these patients didn’t meet anorexia/bulimia criteria because their disordered eating wasn’t motivated by weight concerns at all, but rather, by more focal fears and discomfort related to the food itself or the immediate aftermath of eating. ARFID is an umbrella diagnosis that encompases at least three distinct, but correlated, drivers of restrictive eating. My research started with one of these drivers, so-called “picky eating” (which we now refer to as “selective-neophobic eating,” a more specific description of what this pattern of eating actually looks like). My collaborators and I were some of the first to demonstrate that at high levels, selective-neophobic eating is associated with weight loss, nutritional impairment, and/or clinically significant distress, which could not be explained by any other co-occurring disordered eating. We also described the clinical presentation of selective-neophobic ARFID in two different settings — an adolescent medicine eating disorder partial hospital program, and an outpatient anxiety and OCD clinic.

Kate: You have worked on a number of validated questionnaires assessing different types of maladaptive eating patterns, can you briefly discuss some of your key research projects?

Dr. Zickgraf: When I got interested in ARFID as a grad student, the DSM-5 had just been published. Prior to that, there was no research on ARFID, because it was not a recognized disorder and nobody had previously attempted to create an umbrella that could cover the range of restrictive eating patterns and motivators that were being seen in eating disorder, pediatric feeding disorder, anxiety, GI, allergy, and other clinical settings. In order to start doing research I first had to be able to measure ARFID symptoms, so I developed the nine-item ARFID screen (NIAS) and the ARFID symptom checklist.

The NIAS has three scales, with three items each, assessing the degree to which respondents restrict their eating due to selective-neophobic eating, poor appetite/lack of interest in eating, or fear of negative consequences from eating. The ARFID symptom checklist simply lists and describes the four symptoms that are diagnostic of ARFID in the context of one of the three eating restrictions measured by the NIAS:

- weight loss (or in children, failure to grow taller or gain weight as developmentally expected)

- nutritional deficiencies

- dependence on oral or enteral nutritional supplements

- psychosocial impairment (difficulty functioning in one or more important social roles).

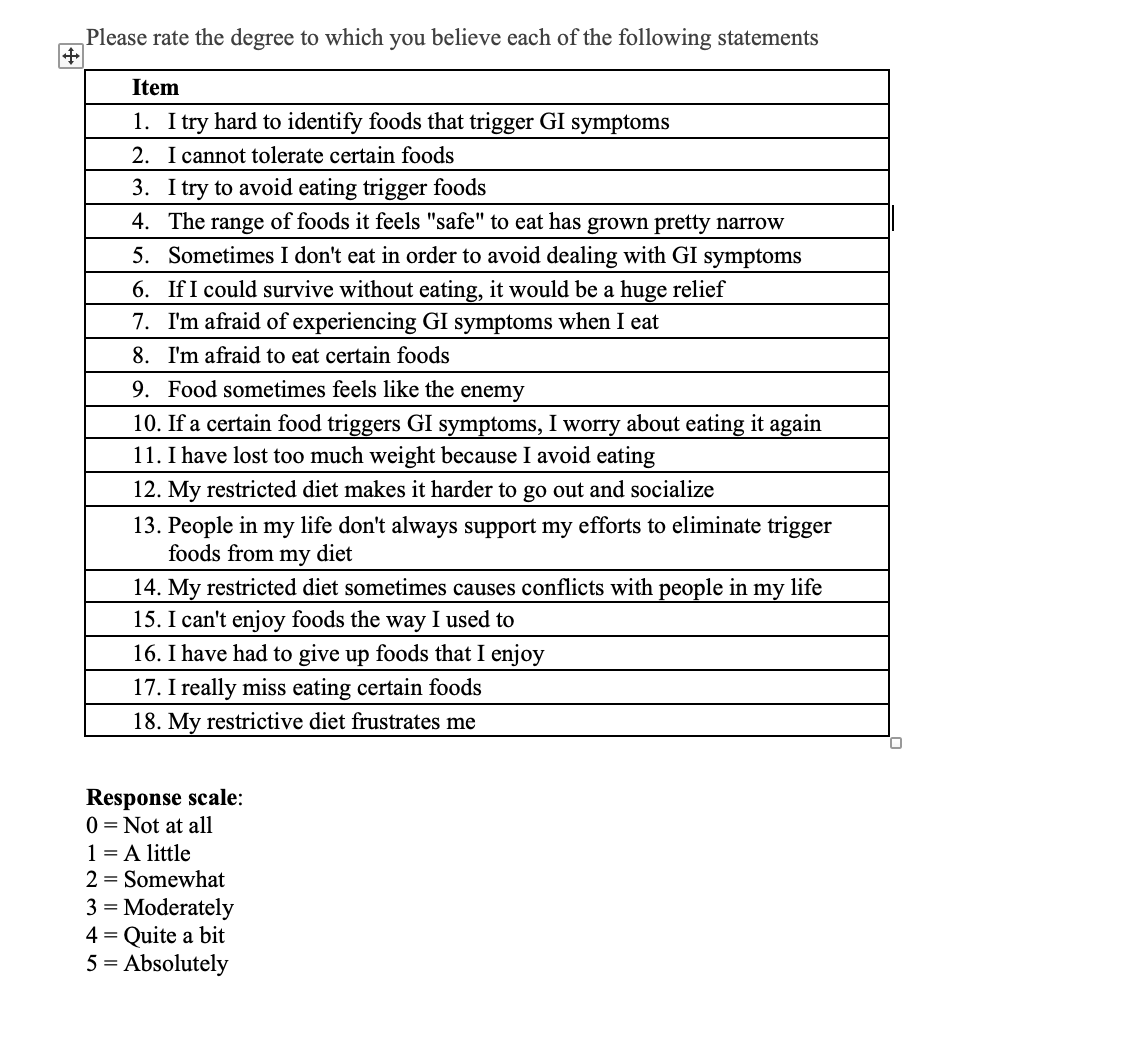

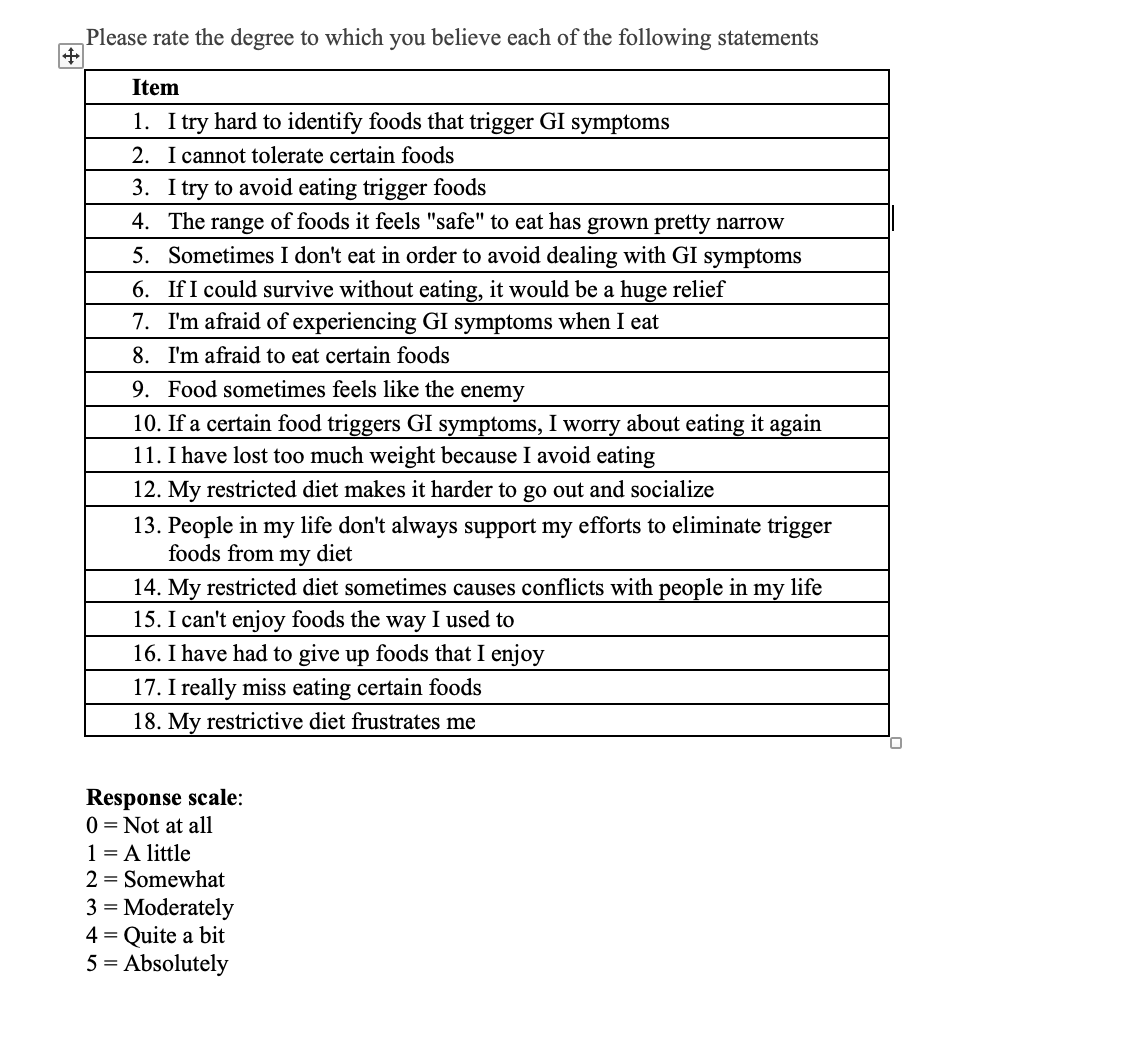

Because it was at the time the only measure of ARFID symptoms, a lot of people adopted the NIAS, and it’s been translated into multiple languages and is now being validated in clinical samples with ARFID (I only had access to convenience samples when I developed it). However, my colleagues who work with GI clinical populations had some concerns that the fear subscale of the NIAS wasn’t appropriate for their populations. I come from an anxiety and OCD background, and when I was developing the NIAS I was thinking of fear-ARFID as being driven by anxiety disorders like choking and vomiting phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder focused on food quality or safety, or functional GI disorders like IBS or globus. In all of these populations, food avoidance and restriction is inherently maladaptive, because there is no underlying physical/medical reason why people with these disorders would be more likely to experience their feared outcomes of eating than the general population. But when people tried to use the NIAS to measure fear-ARFID in populations with digestive diseases or food allergies, it became difficult to tell whether patients’ reported food avoidance on the NIAS was driven by “real” fears and reasonable or medically necessary eating restrictions, or by fear of eating and restrictive eating that went beyond what could be explained by, and what was appropriate to manage, GI diseases. ARFID should only be diagnosed in the latter case. We recently developed the Fear of Food Questionnaire in the hopes of measuring fear-ARFID symptoms in more detail, and with more discrimination between “real” and “disordered” fears.

Fear of Food Questionnaire, click on link for PDF> 18-item FFQ FEAR of FOOD

Kate-Clinical cut off values for this instrument are not yet available, but these questions are suitable to use as a screening (not diagnostic) tool for food fear in GI populations.

Reference: Zickgraf HF, Loftus P, Gibbons B, Cohen LC, Hunt MG. “If I could survive without eating, it would be a huge relief”: Development and initial validation of the Fear of Food Questionnaire. Appetite. 2022 Feb 1;169:105808. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105808. Epub 2021 Nov 16. PMID: 34798226.

Kate: I am particularly interested in avoidant /restrictive food intake disorder in GI conditions. Can you explain what ARFID is—and how it may appear in various subtypes in GI conditions?

Dr. Zickgraf: I’ve since expanded to studying another ARFID presentation, restrictive eating driven by fear of negative consequences from eating. In pediatric eating disorder settings, the most common fears are of choking or vomiting, and the onset of restrictive eating in this population tends to be sudden and extreme, usually triggered by a specific, recent experience of vomiting or choking. A lot less is known about what fear-ARFID may look like in adult populations. I’m finishing writing up a study exploring ARFID in adult participants with vomit phobia, who, compared to kids, seem to have a much more chronic disorder characterized by periods of increased restrictiveness–tied to anxiety, stress, or experiences of nausea and vomiting or related illness–and periods of relatively better eating, but always with some level of concern about eating too much, eating something contaminated, or eating something that may cause indigestion or dyspepsia. With other colleagues, I’ve explored ARFID in adult participants with gastrointestinal disorders, including functional IBS, inflammatory bowel diseases, and celiac disease. In a recent study conducted in a celiac disease clinic we found that a majority of patients met criteria for ARFID, based on fears of eating and experiences of GI symptoms not explained by gluten exposure and disease activity.

Kate: How can a clinician or even a patient themselves differentiate between normal adaptive response to restricting foods that trigger GI distress from ARFID?

Dr. Zickgraf: The best way would be through a referral to a psychologist who can conduct a structured clinical interview. A rule of thumb to help decide when such a referral might be necessary is whether the patient is avoiding foods that they are “allowed” to eat. In the case of IBS, for example, patients are not encouraged to stay on the low FODMAP elimination phase permanently, but rather, go through all 3 phases of the low FODMAP diet in an effort to only restrict food triggers, not all FODMAP containing food. In the case of celiac disease, patients have no food restrictions beyond eliminating gluten. If patients are fearful of eating foods that are medically safe, if they experience GI symptoms that don’t have a medical explanation, if they avoid eating or under-eat, they should consider a referral for ARFID assessment.

It’s also important to consider the possibility of eating disorders other than ARFID in this population. Long-term restrictive eating because of weight/shape concerns or a form of ARFID can cause gastroparesis, chronic constipation, and other GI disorders, and GI patients are more likely than other populations to have a history of an eating disorder. ARFID presentations other than fear-ARFID can cause problems specifically in people who are on medically-managed restrictive diets. Someone who has relatively pronounced selective-neophobic eating may struggle to adhere to celiac disease recommendations because selective eaters tend to eat a high proportion of grain-based foods and struggle to make substitutions for their preferred foods. Patients who lose weight because of an IBD flare and have co-occurring/pre-existing appetite impairment may struggle to eat enough to regain weight after the GI symptoms are managed. Patients who are having a hard time adhering to medical recommendations that involve dietary changes may also benefit from a referral for ED assessment.

Kate: When a clinician diagnosis ARFID in their GI patients —where should the patient be referred? What is the best treatment modality?

CBT has a more explicit focus on identifying unhelpful thinking patterns about food and eating (such as the tendency to make catastrophic interpretations of benign GI sensations) and using systematic exposure with response prevention to help patients to disprove negative beliefs and unhelpful predictions about food and learn to tolerate, manage, and overcome their food and eating-related anxiety without avoiding. Family based therapy (FBT) has a greater emphasis on restoring control over a patient’s eating to parents first, then back to the patient, after ensuring that ARFID–or another ED–no longer has any remaining control. This is done by empowering parents to temporarily make all food choices for their child. Both of these treatments are designed to be short-term (generally lasting 2-6 months), and teach patients and families skills to manage symptoms and prevent disease recurrence in the future. Both CBT and FBT are offered at various levels of care depending on the severity of the weight/nutritional consequences of the eating disorder. Patients should look for treatment at, or community referrals from, eating disorder programs at academic medical centers where ongoing research is conducted. These programs are more likely than programs not affiliated with an academic institution to provide evidence-based psychological treatment.

Kate: This area of food fear and GI conditions is complicated! A diagnosis of ARFID should include clinical assessment along with screening tools, such as the Fear of Food instrument above. Diagnosis should be provided by a clinician that is well versed in the psychological aspects of eating disorders and ideally, one that understands the potential role of ARFID in GI conditions.

Libby Fife

Kate,

Thank you so much! This post was perfect for me to read right now. My therapist is helping me but I am doing a lot of work on my own. I will use this post as a reference. I can’t emphasize enough that EDs are multi faceted, they just aren’t super easy to pick apart. And under eating contributes greatly to GI problems.

Thank you again!

katescarlata

Glad you found this post useful, Libby. Best to you on your health journey!