I attended Harvard Medical School’s Gut Health, Microbiota and Probiotic Throughout the Lifespan Symposium on October 10 and 11, 2018 in Boston, Massachusetts -just last month!

I was very interested to hear Robert Hutkins, PhD, a researcher and professor of food science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln talk about the health benefits of fermented foods. I am all about reporting the science and not the hype so was really hoping to sort out the myths about fermented foods and the science behind their potential health benefits. Here is what I learned…

Let’s start with some basics.

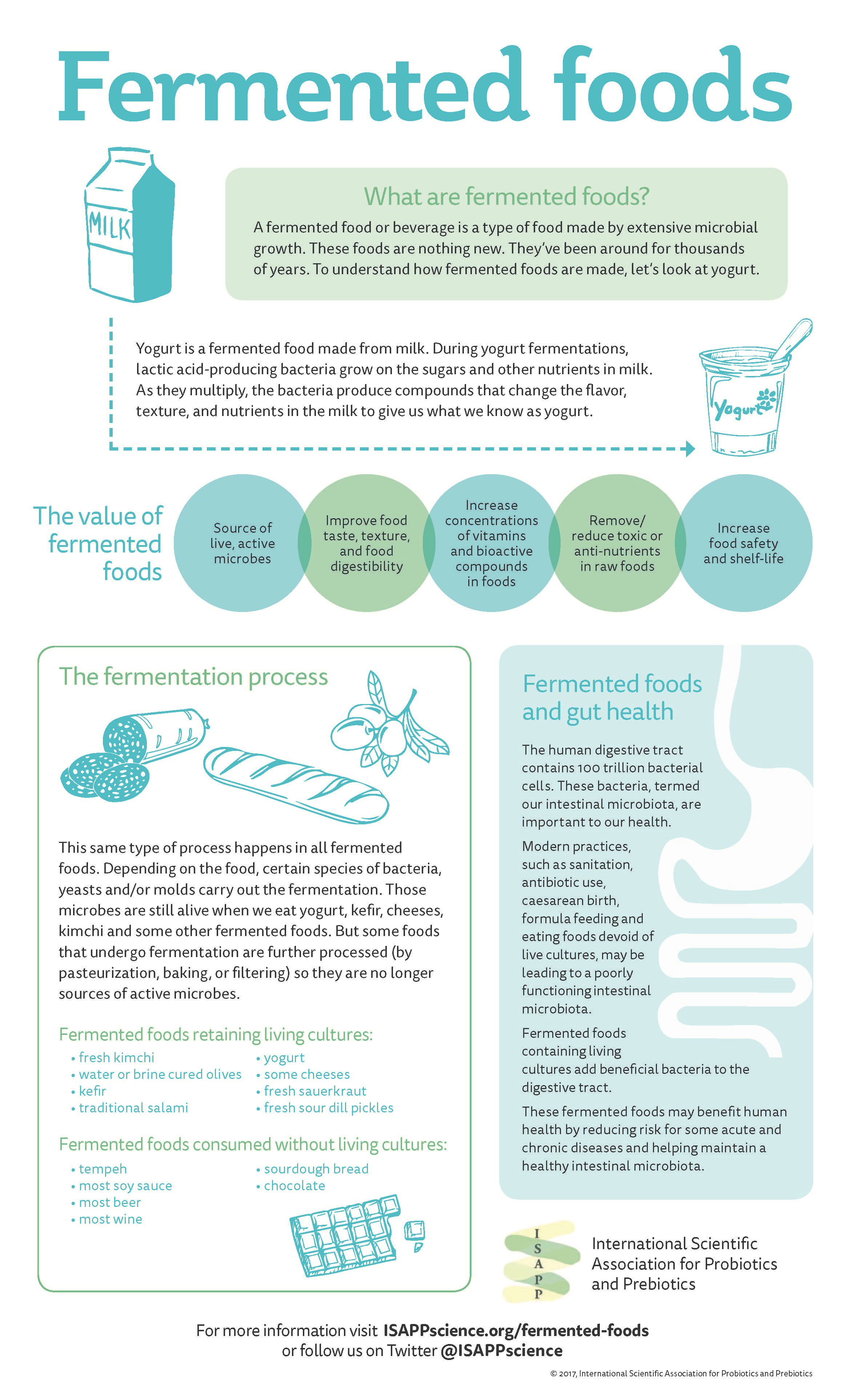

What are a fermented foods?

One of the concepts brought up by Dr. Hutkins was the notion that modern food is mostly sterile! We have become a civilization obsessed with cleanliness. Consumers like sterile food as it, in general, has a longer shelf life! But maybe, we could benefit from ingesting more microbes daily. This commentary, RDA for Microbes-Are you Getting your Daily Dose? provides some thoughts on that–and is well written. Take a peek at the article here.

How long have we been fermenting foods? “Fermentation processes and products are believed to have been developed 9000 years ago in order to preserve food for times of deficiency, improve flavor, and reduce poisonous effects” (Bell 2017).

Fermentation of fruits and vegetables can occur “spontaneously” by the natural lactic bacterial surface microflora, such as Lactobacillus spp., Leuconostocspp., and Pediococcus spp.; however, the use of starter culture such as L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus, L.gasseri, and L. acidophilus provides consistency and reliability of performance (Swain 2014).

What are some commonly consumed fermented foods and beverages? Yogurt, kefir, kombucha tea, tempeh, kimchi, miso and fermented cheeses, sauerkraut and yes, even wine and beer.

What microbes ferment our food? In general, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) including Lactobaccillus, Streptococcus and Leuconostoc are the most prevalent in fermented foods (Rezac 2018). There are many bacteria and yeast in foods naturally. Yeast fermentation produces alcohol and carbon dioxide. Bacterial fermentation produces acid. For instance, many types of bacteria—including LAB , convert sugar or other carbohydrates to lactic acid. Sourdough bread, for example, is often made with a combo of yeast and bacteria.

In short, here are some potential benefits of fermentation:

- Enhanced taste and texture

- Increased microorganism content that appear to improve gastrointestinal health and provide other health benefits, including lowering the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease

- Improved nutritional value:

- Convert unsaturated fatty acids to conjugated linoleic acid, which has anti-inflammatory effects

- Enhanced availability of B vitamins, Vitamin K, magnesium, and zinc

- Creation of isoflavones genistein and daidzein from soy foods

- Reduction of anti-nutrients such as phytates

- Enhance polyphenols which are extracted out of the food by microbe fermentation. (Polyphenols can function as pre-biotics which are food for the health-promoting microbes in our gut).

(Dennett 2017, ISAPPscience.org)

There are few randomized controlled studies on the health benefits of fermented foods. This means we don’t have top level research at this time that shows they are beneficial.

Most health benefits associated with eating fermented foods have been based on epidemiology studies (which often use food frequency questionnaires which have limitations in their accuracy–as individuals self-report their intake–and humans tend not to do self-reporting very well). That being said, eating fermented foods in these association studies have shown a decrease risk of bladder cancer, metabolic syndrome, atopic dermatitis, asthma, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes (Renzaz 2018).

Are ALL Fermented Foods a Source of Probiotics?

Per Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD, executive science officer for the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), “The short answer is no. In part, because the definition of a probiotic per the World Health Organization (WHO) defines probiotics as ‘live microorganisms, which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.’ This means a fermented food must retain enough live microbes to show a health benefit. If a product is heating or pasteurized such as sourdough bread or pasteurized sauerkraut, there is NO live organisms, therefore, there is no probiotics.”

Bread, beer, wine and distilled alcoholic beverages involve use of yeast for fermentation, but the microbes tend to be either removed by filtration or inactivated by heat.

In the US, there is no requirement to state the microbial level of a fermented food. If listed this is purely voluntary. (Renzac 2018).

Dr. Hutkins notes, “Fermented foods does not equal probiotics. The microbes utilized in fermentation are often undefined, non-characterized microbes, but they share similar properties as probiotic microbes.”

This is a great overview about fermented foods as a source of probiotics.

Some commercial fermented food products have added known probiotic microbes added to them. For example, Dr. Sanders, notes the following products and their probiotic microbes: Yakult (L casei Shirota), Activia (Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010/CNCM I-2494), Good Belly (L plantarum 299v).

Key point, even if a fermented food is NOT a source of probiotics as defined by the WHO guidelines, this does not preclude that it can have a positive functional role in health! As noted in the bulleted list above, fermentation by microbes also increase vitamins, inactivate anti-nutritional compounds such as phytates (allowing improved mineral absorption), increases polyphenols–offering health benefit via these mechanisms.

It has been shown in research studies that some microbes present in fermented foods survive digestion and reach the colon. In general, microbes from fermented foods do not last long in the GI tract but they may influence the diversity, structure and function of the microbes that normally reside in the gut (Renzac 2018).

Fermentation and FODMAP Content of Foods

For those following a low FODMAP diet, you may wonder how fermenting foods may impact the FODMAP content of foods. The answer: it depends!

Caroline Tuck, PhD, BNutr (Hons), accredited practicing dietitian and Post doctoral research fellow at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario in Canada, provides the details, “Many forms of food processing, including fermenting, have been shown to alter the FODMAP content of foods. Often food processing results in a reduction in FODMAP content, although this is not always the case and it is possible that in some cases it could increase. The use of traditional sourdough cultures in breads has been well studied and shown to reduce the FODMAP content. Other forms of processing such as pickling have also shown dramatic reductions in FODMAP content such as in pickled onion and garlic. These changes in FODMAP content highlight the importance of individual tolerance testing in patients who are utilizing the low FODMAP diet.”

Fermented tea, called kombucha, is a source of highly fermentable fructans, per the Monash team’s app.

Kombucha is made via a culture called SCOBY, a special combo of yeast and bacteria within a cellulose membrane. Kombucha typically has acetic acid producing microbes as well as LAB. Although touted on the packaging of most Kombucha bottles that it contains live microbes, there have been few scientific studies on the actual levels of microbes in commercial varieties. (Rezac 2018).

While fructans are a prebiotics (food for health-promoting gut microbes), those sensitive to FODMAPs may be troubled by the amount of fructans in this fermented tea. Of course, FODMAP sensitivities are very portion driven and individual, so trying kombucha in smaller amounts and increasing to personal tolerance may be a suitable way to explore your personal tolerance.

Are There Potential Risks to Consuming Fermenting Foods?

Dr. Hutkins notes that fermenting foods overall is quite safe and fermented products have many potential health benefits. For information on how to ferment foods at home safely, I recommend this article by the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP).

It is important to note the fact remains that some of the microorganisms used in the fermentation of food may become harmful under certain undesirable conditions, in particular mycotoxins-toxic substances produce by some yeast associated with with Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus oryzae, Penicillium roqueforti and other fungal toxins.

Some fermented foods can be a source of excess sugar (some Kombucha and yogurt products) and excess sodium (Sauerkraut or fermented cabbage) so keep your portions in check and keep in mind how consumption of these foods fits in with your overall healthy diet. Dr. Sanders notes, “If you rely solely on yogurt for calcium intake vs. milk, this will may increase probiotic intake but you will not get the benefit of the Vitamin D that is added to milk and NOT added to yogurt.”

Bottom line:

- It is important we don’t over simplify the science here. Could eating fermented foods have health benefits? I believe the answer is very likely –YES. But, they are not a magic pill and for those with a sensitive gut–I recommend adding them slowly into the diet to gauge tolerance.

- Fermented foods may be classified more as a “functional food” or a food that have a positive effect on health. In an nut shell: fermentating fiber-rich foods can produce bioactive compounds that may have benefits for our immune system, inflammatory pathways and the way our body handles carbohydrates. For example, the live active cultures in yogurt can reduce the lactose content.

- The modern diet is more sterile than ever. Perhaps adding a little “culture to your life” via fermented foods may provide health benefits.

Update: December 2018

I thought I would add this overview on fermented foods as well–as it provides more information of the state or lack of science and some further information. This appeared in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2019, written by Heidi M. Staudacher and Amy N. Nevin.

References

Bell V, Ferrão J, Fernandes T. Nutritional Guidelines and Fermented Food Frameworks. Foods. 2017;6(8):65.

Dennett, C The Facts About Fermented Foods. Today’s Dietitian 2018;20(4): 24

Rezac S, Kok CR, Heermann M, Hutkins R. Fermented Foods as a Dietary Source of Live Organisms. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1785.

Swain MR, Anandharaj M, Ray RC, Parveen Rani R. Fermented fruits and vegetables of Asia: a potential source of probiotics. Biotechnol Res Int. 2014;2014:250424.

Linda

One thing to keep in mind is don’t over do eating fermented food, if you have never had them you have to start very slowly, increasing it as you go and if it does not upset your stomach. I get too much gas from fermented foods and they clean me out, okay for short term only.

Jolante Wiebe

Loved this article it was really helpful and answered a lot of questions! Do you have any low FODMAP recipes for fermented foods?

katescarlata

Thanks Jolante! My favorite fermented foods is yogurt–and of course, I try to use in some of my recipes! Always with my smoothies and smoothie bowls!

Jolante Wiebe

Thank you Kate. I am dairy free but eat coconut yogurt does that give the same amount as regular milk yogurt would?

2wheeler

Thanks for the article… Lots of good information and links. You mention in your article the”sterile” nature of 21st century food. Beyond sterility most prepared foods contain one or many of myriad preservatives. Are there any studies on the effects of food additives that might compromise out gut biome? I’m thinking those added as preservatives to nearly all store bought items, including breads, meats etc. These products are designed to hinder yeast and bacterial growth in the foods they preserve so what impact might constant consumption have on our digestion? And what about those present in our food unintentionally like glyphosate? We know these inhibit bacterial growth so couldn’t they effect how our gut biome is working?

katescarlata

Good point, but I haven’t dived into this area too much. Emulsifiers in food products are shown in animal studies to impact the gut lining and gut microbiota. But, we can’t always compare mice to humans! There is interest in this area and more research is being done. I try not to be fearful of every bite I make–but instead, try my best to eat foods in their natural state–fruit over juice, whole grains over refined, etc…when possible.