Hello Friends!

Sorry for being off grid for a bit. I blame pandemics (I hope you and your loved ones are staying healthy), other work commitments, writing gigs, and research projects for keeping me a bit too busy and away from posting on my blog.

Good news! I am back!

Most recently, I had the pleasure to mentor Autumn Rauchwerk, a dietetic intern from Teachers College, Columbia University. While working with Autumn, I was reminded of how much I love mentoring and teaching nutrition professionals. I am excited to see the next line of brilliant dietitians share their gifts with the world. Autumn has many gifts–and I am grateful that I had the opportunity to get to know her and work with her. Whenever you are in a teachable moment–as a teacher, a parent, a boss, or as a friend–there is so much learning that both parties can give and receive. As I tell my kids very often, “always look for the lessons”. We can find lessons in almost every interaction we have with another human being and even with our furry friends too.

Autumn and I worked on this post, about Health at Every Size (HAES®). We welcome your thoughts and comments on this topic.

Follow along with Autumn Rauchwerk’s work on her website here. Autumn is also on Instagram here.

Health at Every Size® (HAES®): An important shift in our approach to nutrition

This introduction is by Autumn Rauchwerk

When I first switched careers to study nutrition, I was motivated by the idea that I could help people improve their quality of life by losing weight. A year into my education, something wasn’t feeling right. I was starting to see that focusing on weight loss can result in unintended consequences. Our efforts in healthcare to control weight weren’t working for the majority of people long-term.

There didn’t seem to be some magical solution to good nutrition. It all was pretty obvious – eat a wide variety of foods, plenty of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. If we in the nutrition field had the answers to good nutrition practices and knew what to do to help people lose weight, why didn’t it seem to work? People weren’t getting leaner, and yet they were turning to diets more than ever.

It was then that I stumbled into the approaches of Health at Every Size® and Intuitive Eating and started uncovering the supporting research. Things finally clicked. I realized that perfectionism, attempting to control food and our bodies, were often the antithesis of success, both for happiness and for health. This may go against the grain of everything you have heard about living in a larger body and health. But, if I have grabbed your attention, read on.

In this post, Kate and I will focus on Health at Every Size (HAES)®. HAES is an approach to health that provides an alternative to the conventional weight-centered model through de-emphasizing weight as an indicator of health and promoting size acceptance. HAES works to end weight-based discrimination and focuses on balanced eating, enjoyable physical activity, and respect for bodies of all shapes and sizes. This approach focuses on engaging in health behaviors rather than a number on the scale.

The Health at Every Size® (HAES®) principles are:

Weight Inclusivity: Accept and respect the inherent diversity of body shapes and sizes and reject the idealizing or pathologizing of specific weights.

Health Enhancement: Support health policies that improve and equalize access to information and services, and personal practices that improve human well-being, including attention to individual physical, economic, social, spiritual, emotional, and other needs.

Respectful Care: Acknowledge our biases, and work to end weight discrimination, weight stigma, and weight bias. Provide information and services from an understanding that socio-economic status, race, gender, sexual orientation, age, and other identities impact weight stigma, and support environments that address these inequities.

Eating for Well-being: Promote flexible, individualized eating based on hunger, satiety, nutritional needs, and pleasure, rather than any externally regulated eating plan focused on weight control.

Life-Enhancing Movement: Support physical activities that allow people of all sizes, abilities, and interests to engage in enjoyable movement, to the degree that they choose.

Many people feel resistance to the idea of Health at Every Size® because of everything we have heard about the risks of being at a higher weight. “Obesity” has been linked to some of the most deadly lifestyle related chronic diseases like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer. If this is true, how can we argue for an approach to health that advocates for accepting bodies of all shapes and sizes?

The answer is both simple and immensely complicated, so let’s go with the simple one. Telling people they need to lose weight doesn’t work. There is research to support that 95% of dieters regain at least all of the weight they lost–and 66% of dieters regain MORE weight than they lost. One might think that increasing the focus on weight loss and maintaining a thin image of the ideal body showcased in the media motivates people to lose weight and increases weight loss success. Unfortunately, it doesn’t. It simply glorifies some bodies while putting others down. It enforces pressure, fear of failure, and reduced self-esteem.

Unsustainable and unrealistic body images displayed pervasively on social media, on television, and in magazines marketed primarily to women, likely plays a role in why women are at greater risk of eating disorders or disordered eating. Eating disorder risk has doubled in recent years. One survey study found that those with greater use of social media (including Facebook, Twitter, Google+, YouTube, LinkedIn, Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr, Vine, Snapchat, and Reddit) had significantly greater odds of having eating concerns. Women’s bodies are showcased in media platforms consistently in smaller frames providing a clear disconnect from the norm.

The greater the discrepancy between current weight and desired weight, the greater the risk of eating disorder behavior. Disordered eating presents with eating patterns that stray from the norm, such as limiting many foods or following highly restrictive diets. The overvaluation of being thin is considered to be a risk factor for an eating disorder. One study evaluating the impact of a television series that showcased thinness and stigmatized obesity revealed disordered eating indicators were significantly more prevalent following exposure to the show.

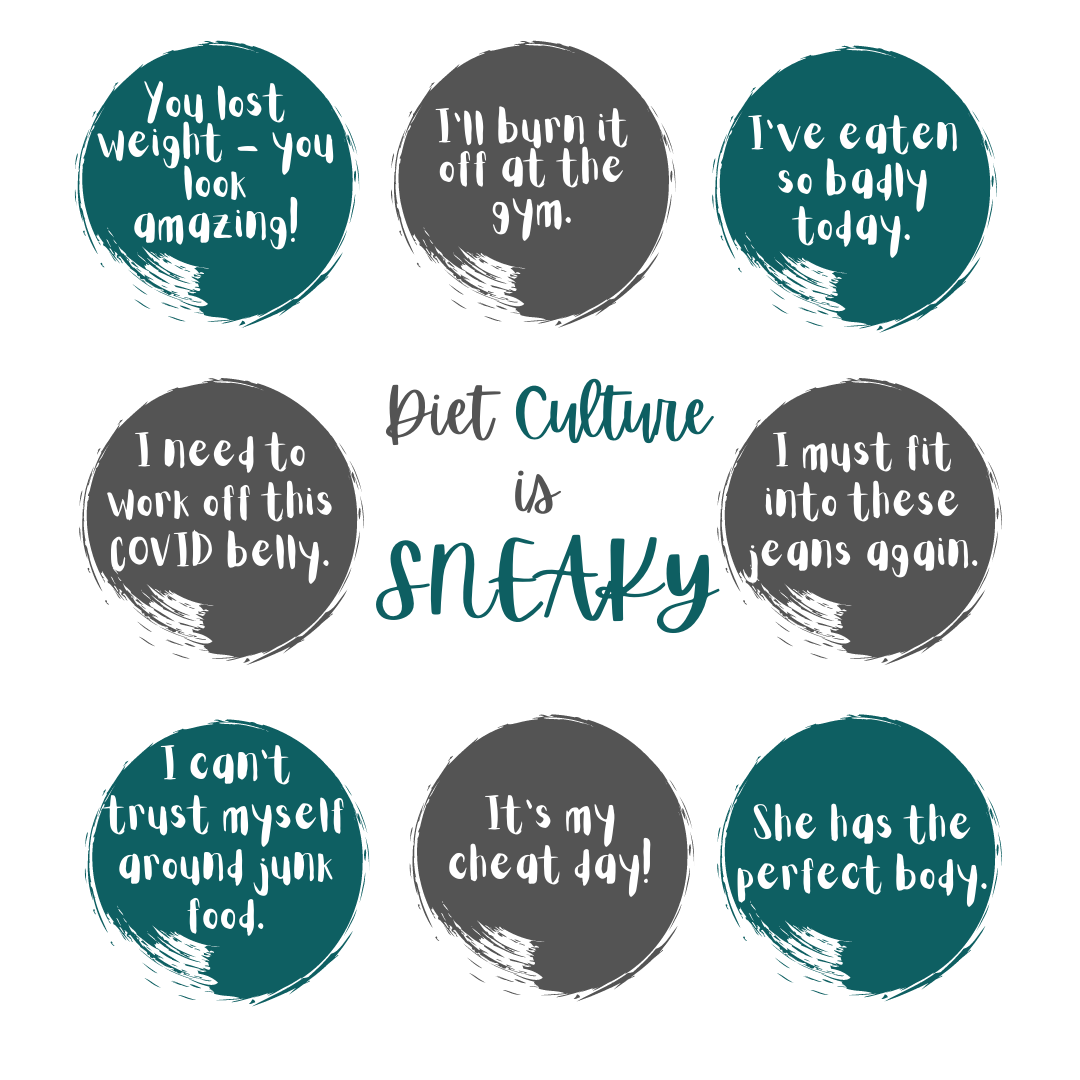

Diet culture is all around us.

While these comments noted in this graphic are common in our culture, they speak to the very nature of how dieting has infiltrated our culture here and now.

- Most of us have said or thought more than one of these things with the best intentions. The problem is, they focus on judgment and comparing ourselves to other people or to a “superior” version of ourselves. These ideas promote the notion that we need to “earn” our foods, and that self-control and restriction are signs of morality.

- Diet culture places an emphasis on weight above all else, valuing body size more than well-being. It often involves adapting restrictive eating and rigid exercise habits, claiming that they are for health reasons, when these behaviors are really about achieving a more “ideal” body.

- It is important to emphasize inherent self worth and self care rather than believing we need to change in order to be worthy. It is also important to not make assumptions about anyone based on their body size or use our body size or food choices to measure our worth or health status.

Many people will lose weight on a diet for a period of time, maybe even 6 months or a couple years, but then the weight comes back. And how do people respond to these diet failures? They are led to believe that if they regained the weight, it was because they failed at the diet. The diet worked, but they couldn’t stick to it well enough. It was their fault.

In reality, people have natural set ranges for their weight – a range of weight their body wants to be at, deems healthy, and will do what it can to maintain. When someone restricts calories in some way, their body thinks it is starving and fights back by slowing its metabolism and craving higher calorie foods. This is not a curse but rather our bodies’ built-in survival mechanism.

Weight loss followed by weight gain often leads to a change in body composition. During the weight loss phase, muscle and fat are lost by the dieter, but when the weight is regained, it often comes in the form of fat. The person then has more fat and less muscle. This impacts metabolism, as fat is less efficient than muscle at burning calories. When the person goes on another diet, the same thing can happen, a process called weight cycling, which can lead to greater long-term health risks than being at a higher weight to begin with.

Here are some interesting facts about weight and health risks… people in the “overweight” BMI category have longer life expectancies than people in the “normal weight” category. Additionally, for those who already have chronic disease, research shows that a higher BMI is beneficial in their prognosis. Furthermore, 1/4 of “normal weight” people may be “unhealthy” – or at higher risk of chronic disease based on measures like blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol. Health is much better assessed by factoring in genetics (which influence weight as well as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease risk), measuring blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol, and assessing stress, sleep, eating and physical activity patterns.

People who are “obese” have been called the last acceptable targets of discrimination. Even though weight is largely genetically determined and does not tell us anything about someone’s lifestyle, it is deemed acceptable to make assumptions about someone’s behaviors based on their weight. People in larger bodies are berated by doctors to the point that they may avoid visits and treatment, are constantly judged for their eating choices, struggle to find clothing and seats on planes that fit their bodies, are labeled as lazy and unattractive, and the assumption is that they have earned their fatness and that thin people have earned their thinness. Besides the inaccuracy of these assumptions, experiencing weight stigma, or negative attitudes or treatments based on their health, can itself lead to increased chronic disease risk and poorer lifestyle choices. Weight stigma contributes to increased eating and reduced exercise motivation and is linked with anxiety, binge eating, reduced self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction.

The alternative to all of this is adopting a Health at Every Size® Approach to health. Research shows that the HAES approach can help people improve blood pressure, blood lipids, disordered eating-related behaviors, and psychological parameters like self-esteem, body image, and depression without contributing to weight gain or any adverse health risks. Celebrating body diversity does not glorify fatness or reinforce unhealthy behaviors, it encourages people to accept and respect their bodies so that they will be motivated to care for them. It teaches people to trust their bodies and tap into what their bodies are telling them so that they can eat and move in a way that feels good and ultimately promotes health.

The Intersection of HAES for GI conditions and Evidenced Based Nutrition: How does a low FODMAP diet fit

Understanding that most of the readers of this blog are interested in gut health, IBS and the low FODMAP diet, let me briefly explain how the intersection of HAES and an evidenced based nutritional approach work together. The low FODMAP diet is a 3 phase science-based intervention shown to manage GI symptoms in individuals with IBS. It is a nutritional approach intended to help with IBS symptom relief and is not intended to be used to aid weight loss.

For someone who is using nutrition as a tool to address their GI symptoms, it is important that they are paying close attention to how their body responds to different foods. The great thing about the low FODMAP diet is that it does not eliminate any food groups, does not control portion sizes, and is a temporary elimination diet that involves adding foods back in and paying close attention to which foods trigger symptoms and which foods work well for that person. If you find that your diet is adding stress or you are becoming hyper-vigilant with your diet, consult your healthcare provider to help guide you. Nutrition can be a great tool for GI symptom relief, but it is far from the only treatment.

People who experience GI conditions are at greater risk of disordered eating behavior. In fact, almost ¼ of people with GI conditions engage in disordered eating. This is an area that is currently being explored more to best guide patients in their clinical care. Furthermore, eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, can result in GI symptoms and abnormalities in gut function. When there is a focus on weight loss, it’s common that an individual will shift their attention away from paying attention to their body and instead focus on trying to change their body. With body acceptance, greater attention can be placed on tuning into focusing and respecting their body’s messages and reactions to foods to best figure out what foods trigger symptoms. This can help the person to make educated choices about how they choose to eat and in a way that makes them feel good.. Working with a dietitian in this process is very helpful.

If you’re interested in more information about HAES, here are a few sites to check out:

https://www.sizediversityandhealth.org/

https://weightinclusivenutrition.com/

References:

-

- Becker AE, Burwell RA, Gilman SE, Herzog DB, Hamburg P. Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:509-14.

- Dollar, Emily et al. “Do No Harm: Moving Beyond Weight Loss to Emphasize Physical Activity at Every Size.” Preventing chronic disease vol. 14 E34. 20 Apr. 2017, doi:10.5888/pcd14.170006

- Harer KN. Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Disordered Eating, and Eating Disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y). 2019;15(5):280-2.

- Galmiche M, Dechelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1402-13.

- Lainscak, Mitja, et al. “The Obesity Paradox in Chronic Disease: Facts and Numbers.” Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, vol. 3, no. 1, Mar. 2012, pp. 1–4. PubMed Central, doi:10.1007/s13539-012-0059-5.

- Mathew, Hannah, et al. “Metabolic Health and Weight: Understanding Metabolically Unhealthy Normal Weight or Metabolically Healthy Obese Patients.” Metabolism, vol. 65, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 73–80. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.10.019.

- Rauchwerk, Autumn, et al. “The Case for a Health at Every Size Approach for Chronic Disease Risk Reduction in Women of Color.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Sept. 2020. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2020.08.004.

- Sidani JE, Shensa A, Hoffman B, Hanmer J, Primack BA. The Association between Social Media Use and Eating Concerns among US Young Adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):1465-1472.

- Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(6):543-8.

Ella-Kate Trice

So good, Kate! I’m an ACE Certified Personal Trainer and Weight Management Specialist, and I couldn’t agree more with your post. It’s truly about helping clients find that inner motivation to change, in a supportive, empowering environment – not just giving them a one-size-fits-all plan. Thank you for bringing clear, research-based logic into this discussion.

katescarlata

Thanks for chiming in Ella-Kate!

Christy Widman

Love that this has been addressed in this forum. Diet culture is no one’s friend. Thank you for this!

katescarlata

Thanks for your kind comment, Christy.